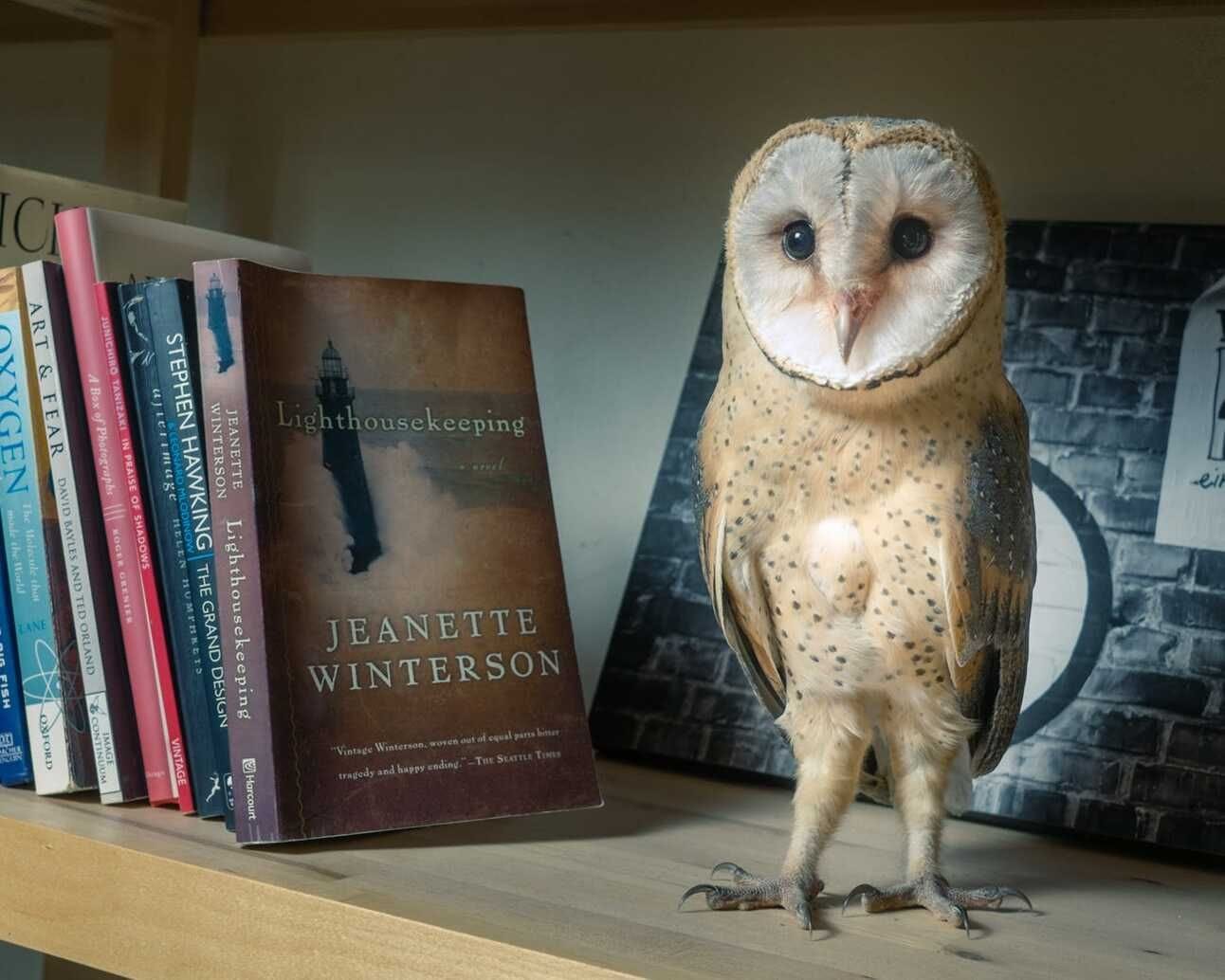

Never in my life had I thought we’d live with an owl. But here I am, working on my next book, with Peppa our rescue barn owl snoozing on my old loom behind me.

It all began on July 1, when we joined the local wildlife guy to ring the barn owls in the church tower nearby. One of the owlets was tiny. It’s normal for barn owlets to differ in size because they hatch approximately 48 hours apart.

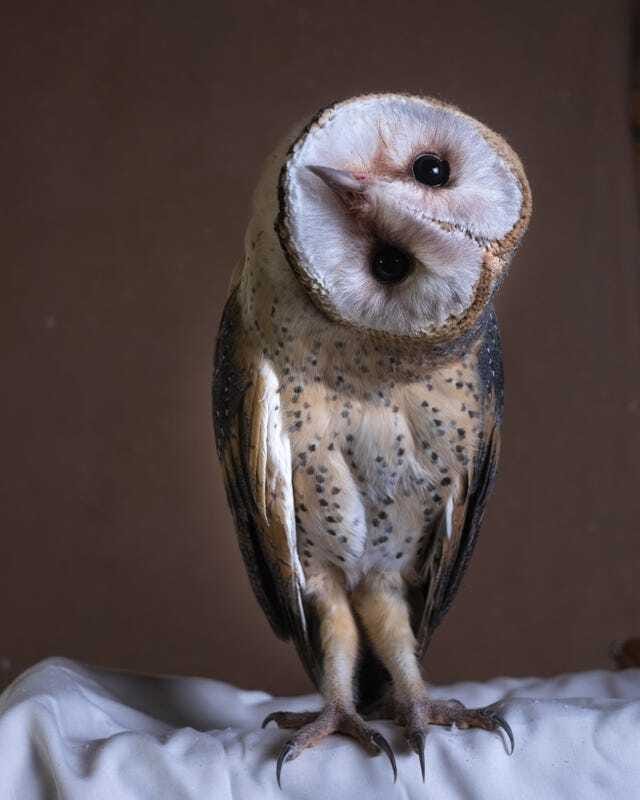

But the tiny one was clearly malnourished. At 3 weeks of age, it should have weighed more than 200 grams but was less than a third of that. We decided to take her home with us, fatten her up for a week, and then put her back to her siblings.

As Peppa (we named her Pepparkaka, Swedish for gingerbread cookie) very slowly gained weight, the young kestrels living right next to the barn owlets died one after the other from trichomoniasis. Soon, Peppa showed first signs of this highly infectious disease. We started treating her asap, but that also meant she couldn’t go back to her siblings for another week.

She responded well to the medication but didn’t grow as fast as we’d hoped. There’s only so much food fitting into a small owlet’s stomach. Meanwhile, the wildlife guy was looking for barn owl nests with owlets of Peppa’s size but unfortunately found none. She was the tiniest barn owlet in the area.

So Peppa had to stay. She’s the reason why we launched a licensed owl rescue & rehab. But that’s also when we got worried about human imprinting. Would wild barn owls accept her? Would her own family chase her away when she started flying? Would she even know that she’s a barn owl?

Peppa grew and began to look more like an owl and less like a hairy troll. She had free access to our house and the outside at all times, and she spent her nights watching her barn owl family from the open bedroom window. She ate LOADS (where the hell did she put all that?) and, to our amazement, she loved cuddles. Although barn owlets enjoy physical contact 24/7 and often engage in mutual preening, it was fascinating and heart-warming to see that she bestowed all that affection on her human family.

As owl parents, we learned a lot (for example that owls love to bathe), had only one disagreement with our owl child (whether or not dead mice should be stored under our bed), wiped away lots of poop, and collected countless pellets. We enjoyed every minute of it.

When Peppa stayed away the first night, we could barely sleep. We were so proud of her when she returned the next morning, exhausted and happy. One of her siblings even flew through our bedroom window to nip Peppa’s beak. Even though she was still 2 weeks behind the other owlets, contact with her family was established and she started flying with them.

One morning, Peppa did not return. We knew this had to happen at some point, but she wasn’t able to hunt yet. Worried and heartbroken, we searched the garden and the house for more than an hour, because we didn’t know if she was all right. But when we looked up at the barn owl nest in the church tower, we saw Peppa bobbing her head and wondering what the fuss was all about. Although her family fully accepting her meant a successful owl rehabilitation, it was sad to say goodbye.

Without Peppa, our house felt empty and quiet.

BUT YESTERDAY AT 5AM THIS CRAZY LOVELY OWL RETURNS, TOTALLY EXCITED TO SEE US!

She ate and spent the day snoozing on my old loom – her favourite perch, then flew off again at nightfall.

Thanks to Peppa, we’re now a patchwork family of owls and humans. We don’t know how long she will keep visiting, but we treasure every moment with this affectionate and intelligent bird.

Barn owls can get over twenty years old in captivity. In the wild, they often make it to only two years of age. Humans are their most frequent cause of death: they starve because of manicured landscapes, are hit by cars, or drown in rain water barrels and swimming pools. To learn how to help wild barn owls, click here.